Last week I was in Bangalore. I met an old friend, Jana Reddy, who took me to his farm in Palakkodu, Tamil Nadu, over 100 kms away.

And he is what the new sons of the soil look like.

He is a techie, responsible for a portfolio with over 3000 team members. Well, he is more of a technocrat, less of a techie. Married to a techie. His son goes to college in another city. Aging parents live in a lovely area close to his high-end apartment complex. Loving son, affectionate husband, responsible parent, giving friend. A down-to-earth person.

He was like this in 1996, when I first met him. And today too, he is as down-to-earth. More so, in many ways.

Because he chose to go back to the land. About 10 years ago, a harsh conversation with a business head made him see that there was more to him than climbing the ranks in a large IT company, however lucrative. He started thinking about what he’d want to do post-retirement. And it was the memory of his school-time summer vacations spent in his native village that held the answer.

Find some land, do some farming. Not just own some farmland, and be a consumer of it. But work the land, and be one with it. Sixty years of age would be too late to start, he reckoned. “I need to start now!”

That set him off in pursuit of buying some land. Ten years later, he owns 8 acres in Tamil Nadu.

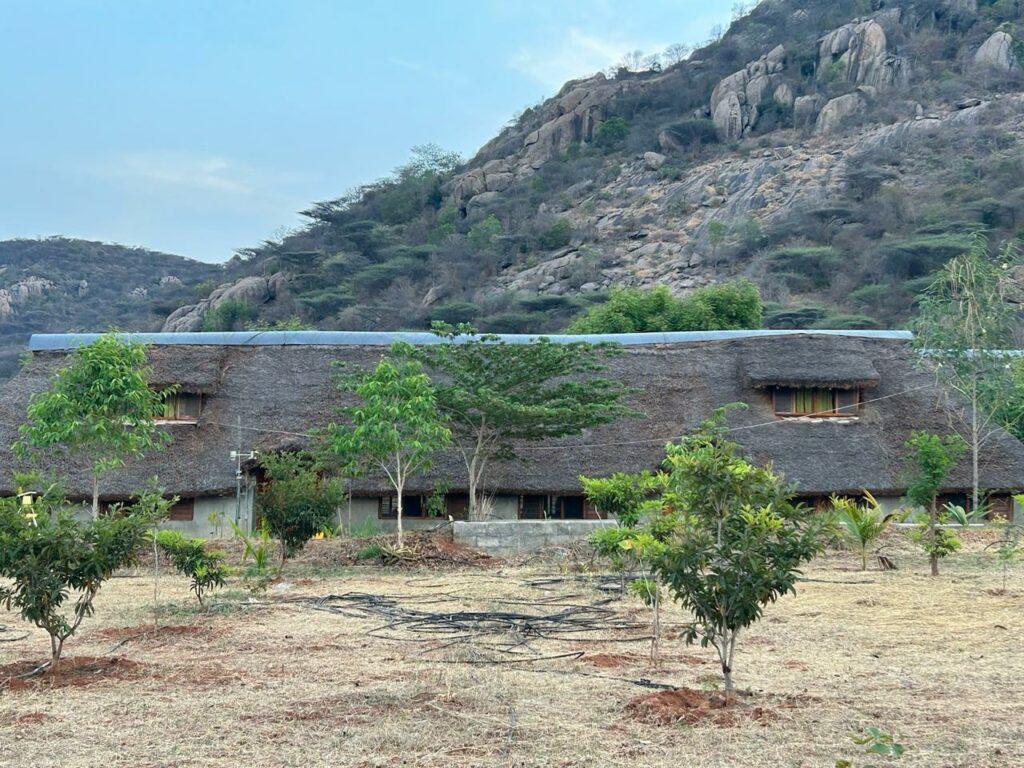

Jana has built a house with mud walls and a thatched roof, fitted with all modern amenities. It has two wooden lofts; one is his sleeping area, and the other is his remote work setup.

He has a barn to house his goats and store his farm equipment. He has some poultry, most of which were killed by a leopard recently. He is building a stepwell.

He is not a farmer by education. He is learning as he goes, experiments, fails, pays dearly for it all, and then sees some success.

Jana’s farm is not a neat, flat piece of land. It is land that starts at the foothills and runs down towards the town. He chooses to keep it like that, working with the large rocks there to create boundaries and safety. He is using the slopes of the land to do rainwater harvesting. Sure, there are borewells, but the rainwater holds the power to sustain life. The lack of water is worrying now, he is hoping for rains to start soon.

He looks at the hills rising magnificently, providing a beautiful backdrop to his land. And wonders why some trees on the hills are all green and thriving, while some others are burnt down. He wants to understand how that happens, and bring that learning to his farm. He knows that there’s a way that nature works, and he wants to align with that.

Even the driveway he has conceptualized follows the lay of the land, so one can feel the essence of the land as one drives in.

Standing at the highest points of the farm, you can look down to the house and the barn. You will be excused if you miss spotting them, because the roofs and the walls just blend with the landscape. No jarring colours, no paints, no artificial decorations. Just oneness.

He reads books on farming, talks to farmers, and identifies what suits best for the land he is the custodian of. Sometimes it means going against the conventional wisdom, and you can see him struggling to get the farm workers to listen to how he wants things done. It’s probably the only time I have seen him upset, and it’s not even obvious; such a gentle soul.

Everything is organic in the farm. There are coocunut trees, areca, figs, mangoes, aloe vera, brinjals, green chillies, herbs, bottle gourd, lemons, cherries, flowers, agatti, tamarind…

The only hint of chemicals is the anti-termites he has used to protect his wooden lofts from harm.

All the garbage from his apartment and that of his parents’ house is separated five ways, and most of it is brought to the land to enable composting.

His ways of living are less consumptive now, he says. Most of the money he earns goes into the land. Pre-covid he had built a solid business selling organic produce to about 250 families in Bangalore. Covid changed all that. He is into pleasure farming now, he says. “I do what I like to do!”

I hear that as, “I am experimenting to see how I can work with nature so the land is bountiful, beautiful.”

Many of the old sons of the soil belong to a certain area, are hardcore farmers; they know the ways of the land and have agriculture in their blood. The new sons have lived in the city most of their lives, and look for land to work with, wherever they can get it. They probably have tech in their blood, but land in their soul. It’s a calling, perhaps not an occupation for them. It’s a choice, not a lineage. It’s an intention, a fierce one at that. To be a custodian of the land, to do right by the land.

When there are such sons around, the Mother will be okay. She knows that her sons have returned. All is well.